Reader Survey

The Ongoing Impact of COVID-19 Policy in Education

It’s no stretch to say that the public policy

response to COVID-19 has changed and will continue to change

every aspect of education in K–12 and higher education for the

foreseeable future.

What once seemed a short-term emergency akin to “snow

days” has grown beyond most people’s wildest fears. Every state in

the nation shut down its K–12 schools last spring, and, with the

exception of one state (Montana), they all stayed closed through

the end of the school year. Colleges and universities closed one by

one. Some reopened only to have to close again weeks later.

We polled our readership to learn of the experiences taking

place across the nation and get a glimpse of what’s being planned

going into the spring 2021 semester and beyond. We heard from

facilities planners/managers, administrators, information technology

professionals, faculty, policymakers, architects, maintenance

professionals and engineers from around the country.

The impact on facilities planning, design and management

has been profound. “We were not prepared for anything like

this,” one K–12 education respondent told us. “We’re doing it all

on our own; every school is doing something different,” said another.

“The lack of guidance and support from the national level

is appalling.” One higher education respondent said, “[Campus]

will never fully reopen in the environment that we once knew.

COVID-19 has changed the very face of how instruction is given.”

Photo © Panchenko Vladimir

Delivering Instruction in the Fall

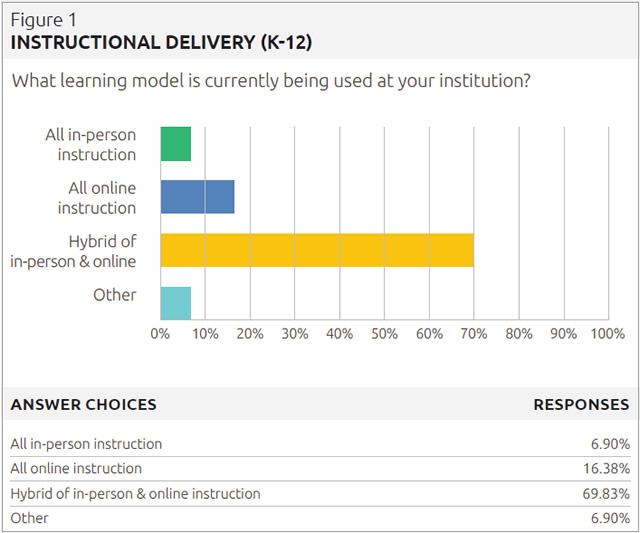

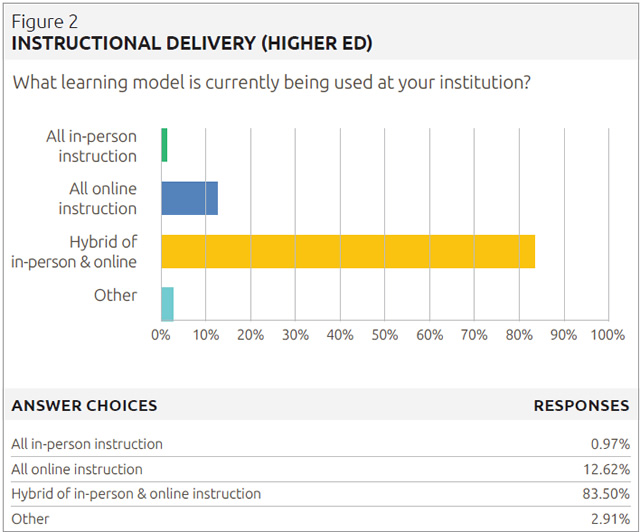

Overall, in both K–12 and higher education, the vast majority

of respondents reported that their institutions have been

using a hybrid model of instruction — about 70 percent in

K–12 education and 83.5 percent in higher education. All-online

instruction was the second-most-popular response, at

16.4 percent in K–12 and 12.6 percent in higher education.

In K–12, about 7 percent reported they were doing in-person

instruction, compared with less than 1 percent in higher education.

The remainder were doing variations — for example, mixed

by grade level or offering students the choice of either all online

or all in-person instruction. Some switched models partway

through the semester.

“We are primarily teaching online courses, no more than 25

percent face-to-face, and most of those we are offering an option

to participate via zoom,” said one respondent in the higher ed

space. “Most of our students have obeyed the rules of face masks

and social distancing. We’ve been having a rolling 14-day average

of between five and 14 infections, although we are relying

on self-reporting because we are not testing. Our IT department

has offered students resources for those with poor or no Internet

connections or who lack cameras on their home computers. We

are doing well.” (See Figures 1 and 2)

Remote Learning

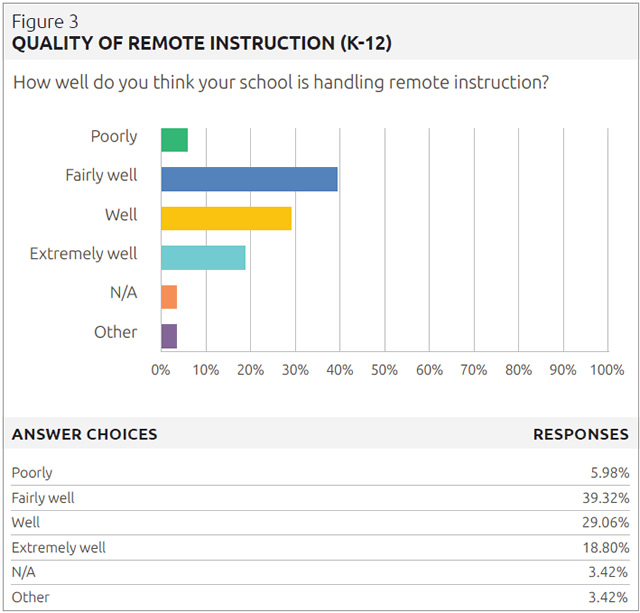

Among those whose institutions are offering remote instruction, most rated the management

of that instruction positively. In K–12, more than 90 percent of respondents said

their institutions were doing fairly well, well or extremely well at handling remote instruction.

Just 6 percent said they were doing poorly. The remainder were either undecided or

deferential given the circumstances. One resspondent said their institution was doing “as

best as can be expected under crazy circumstances.”

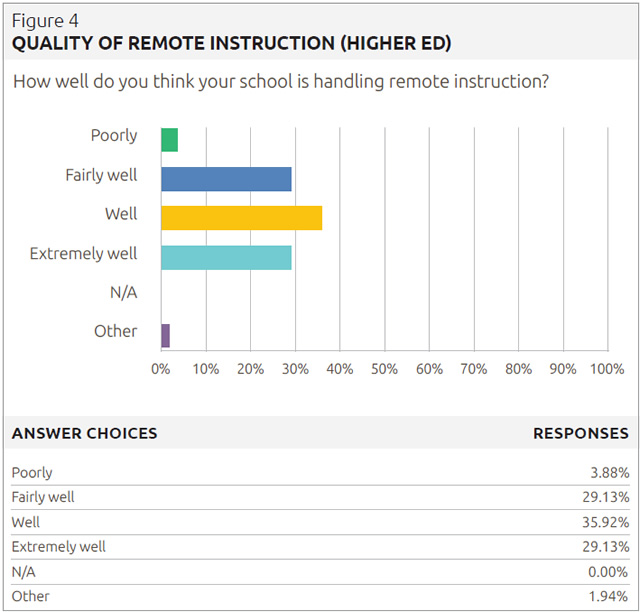

In higher education, more than 94 percent said their institutions were doing fairly

well, well or extremely well. Just 4 percent said they were doing poorly. Another small

percentage reported mixed feelings. (See Figures 3 and 4)

Facilities & Infrastructure

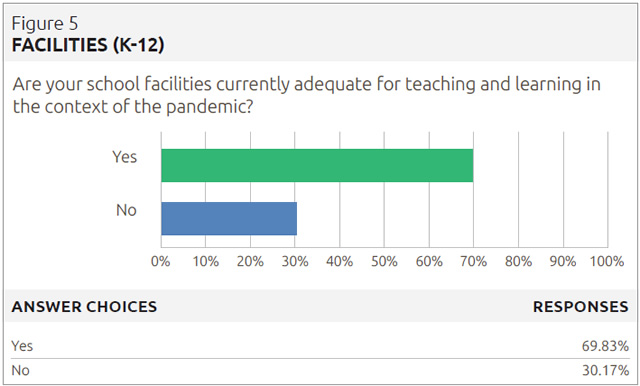

When it comes to facilities, most in K–12 and higher education said that their

existing facilities are adequate for delivering in-person instruction — 70 percent in

K–12 and nearly 80 percent in higher ed.

The biggest complaints about their

schools’ facilities among K–12 respondents

were:

- The size of the classrooms;

- The number of classrooms;

- Difficulty with social distancing;

- Difficulty cleaning or finding cleaning

products;

- Lack of technology resources;

- Busing; and

- Ventilation.

“The classroom is not big enough for

social distancing, and we do not have resources

for everyone to have all they need

without sharing,” according to one respondent

in K–12.

Some offered the caveat that, while facilities

are adequate now, they would not be

as more students begin attending in-person.

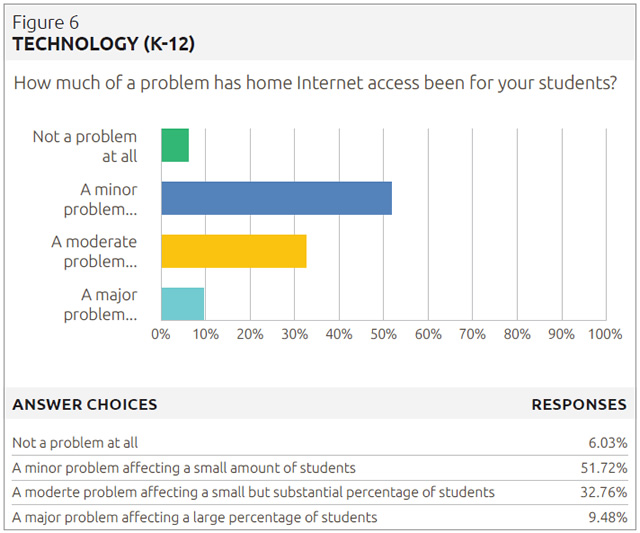

On the technology front, home internet

access is somewhat an issue for K–12, although

only 9.5 percent characterized it as

a major problem affecting a large percentage

of students. A third characterized it as

a moderate problem affecting a small but

substantial percentage of students. Most

(52 percent) said it was a minor problem

affecting a small percentage of students.

Six percent said it was no problem at all.

At the time of the survey (October/November 2020), 18 percent of K–12 respondents

reported that their institution

was forced to close at least once during

the fall semester owing to COVID-19 cases.

(See Figures 5 and 6)

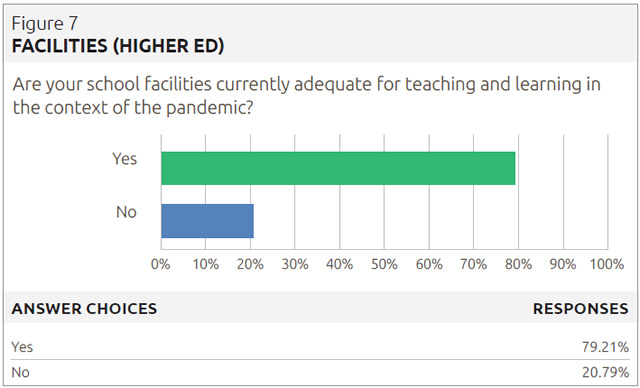

In higher education, where nearly 80 percent

of respondents said their facilities were

adequate, the most significant problems

among respondents were space and technology

infrastructure. Some, whose students

had not all returned to class at the time of

the survey, worried that facilities would be

inadequate but couldn’t be sure at the time.

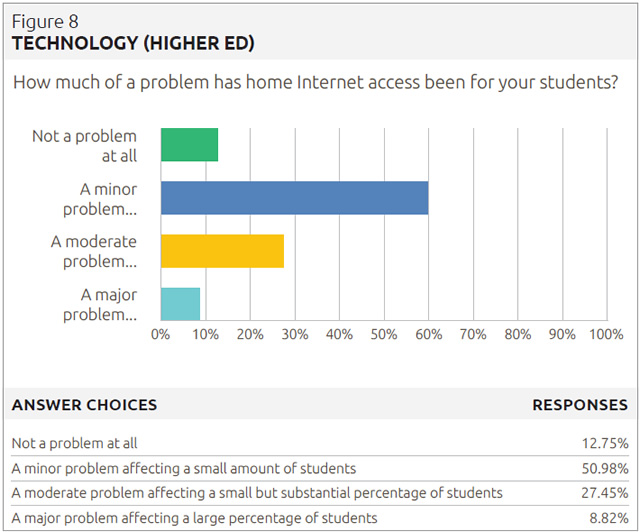

As far as technology is concerned,

home internet access was even less of an issue

in higher ed than in K–12. More than

twice as many respondents (12.75 percent

in higher ed versus 6 percent in K–12) indicated

that home internet access was not

an issue at all. The majority (51 percent)

said it was a minor problem affecting few

students. About 27 percent said it was a

moderate problem affecting a small but

substantial percentage of students. And

nearly 9 percent said it was a major issue affecting a large percentage of students.

One respondent described their approach

to adapting existing facilities to

the needs of the pandemic: “We have

limited in person classes — mainly those

requiring hands-on instruction. We have

established procedures for cleaning between

classes and have scheduled breaks

between classes to allow additional cleaning.

We have deployed extensive hand

sanitizing and mask stations and have

marked public areas thoroughly for social

distancing.” (See Figures 7

and 8)

Takeaways, Lessons

Learned & Looking Forward

We asked our audience the following

open-ended question: “What has been the

biggest takeaway you’ve learned so far with

regard to school reopening?” Responses

to that question were, to say the least,

scattered all over the board. A few trends

emerged from their responses, however.

Among those who were strong on remote

learning prior to the pandemic, the

perception was that remote was working

well for students and would continue to

grow in the future. But among those who

were primarily face-to-face prior to the pandemic,

remote learning was perceived as a

poor substitute for in-person instruction.

There was widespread recognition of

the need for flexibility and patience.

Technology proved to be a huge help

to education professionals, although many

reported that they needed more access to

technology tools. In fact, when asked what

were the most helpful tools used this fall

semester, digital tools were by far the most

frequently lauded. Among the most frequently

cited helpful tools were:

- Zoom;

- Google Classroom;

- Microsoft Teams;

- Learning management systems such as

Blackboard and Canvas;

- Laptops and Chromebooks;

- WebEx; and

- Screencastify.

Of non-digital tools, general cleaning

products, masks and electrostatic sprayers

were most frequently cited.

Looking ahead to procedures for the spring, in both K–12 and higher education,

respondents generally agreed that

there will be a continued emphasis on

online learning, continued social distancing

and ongoing rigorous cleaning procedures.

By far, however, the most popular response

to the question of what new procedures

will be implemented in spring was

“not sure.”

When asked what the most significant

challenges schools, colleges and

universities still face, the most common

responses across both K–12 and higher

ed were:

- Shortage of teachers and staff;

- Class size;

- The inadequacy of remote learning versus

face-to-face;

- Adherence to safety procedures, such as

wearing masks continually and maintaining

physical distance;

- Student disengagement with two commonly

cited causes: the remote learning environment and, in

the case of in-person instruction, the wearing of masks;

- Lack of funding; and

- Lack of leadership.

Several survey participants lamented the challenges of overwork

and mental and physical strain in these circumstances. “Educators

have put everything on the line,” one K-12 respondent

said. “Our families, our mental and physical health ... have all

been impacted. Many of us are so exhausted, beaten down and

frustrated that we will leave the profession prematurely.”

Equitable access to technology was also widely cited as a

major challenge by several respondents. “We wouldn’t be comfortable

teaching in school if one child is left in the hallway and

can’t access the class, but when we go virtual there doesn’t seem

to be the same urgency when students are locked out of classes

due to lack of devices or not having the wherewithal to use the

devices they have,” one K-12 respondent noted.

The keys to success this spring? According to many: budgeting

for additional technology, providing internet access for

those who need it and providing training to faculty and staff in

the technologies they need to deliver instruction in remote and

hybrid learning environments.

Methodology

The survey was conducted among Spaces4Learning readers

online over a three-week period in late October through early

November. Two-hundred twenty-two surveys were completed —

104 from higher education, 118 from K–12.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of Spaces4Learning.